Our mission

HEC Imagine enables talented students from war-torn regions to complete a Master’s degree at HEC Paris. We are also aiming to shape an ecosystem for business and peace on our HEC Paris campus and beyond.

Our Imagine Fellows

We have so far welcomed students from Afghanistan, Syria, and Ukraine and look forward to new Imagine Fellows joining HEC Paris in the upcoming months.

Latest news

On the 7th of October 2023, a 6.3 magnitude earthquake struck West Afghanistan, impacting more than 50,000 people, and killing 2,000.

The 4 Afghan students from HEC Imagine mobilised their contacts on the ground to find a solution to distribute food, clothes and tents.

In less than a week, the association raised 1,500€ of solidarity fund to help the affected populations.

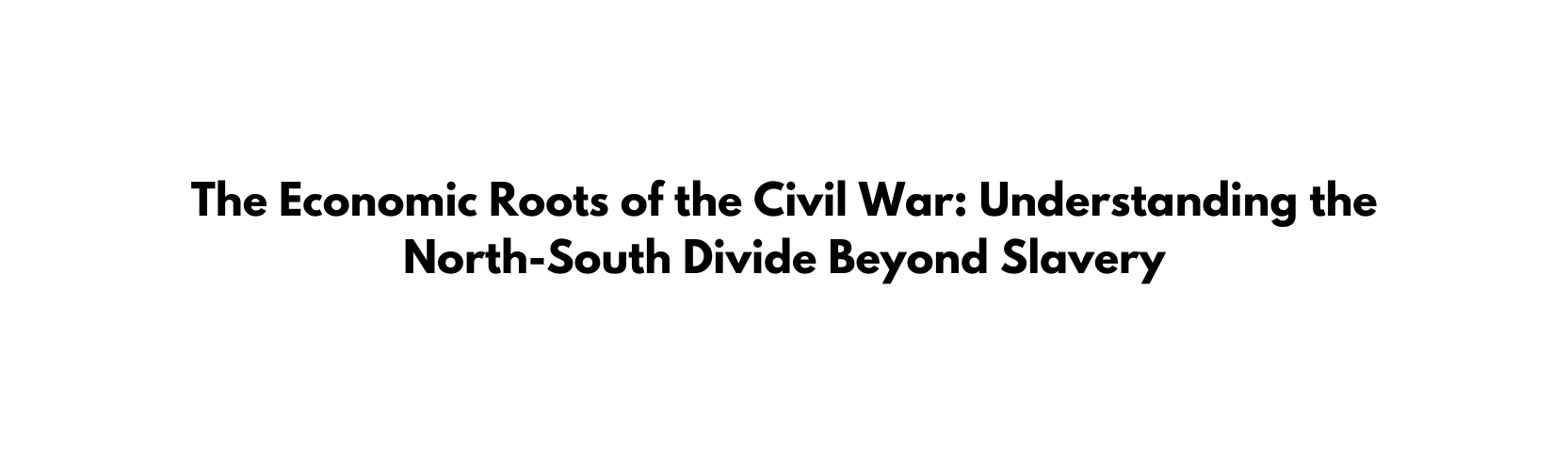

Few events have left as profound a mark on the American national consciousness as the devastating Civil War of 1861-1865, better known as the “guerre de Sécession” in French. To explain the origin of this national tragedy, the commonly held belief is that it stems from a deep disagreement over slavery between the abolitionist Northern states and the pro-slavery Southern states. Although slavery played a crucial role in this conflict, it alone does not fully capture the complexity of the origins of this war. For instance, some slave states did not secede and remained in the Union. These "border states" include Missouri, Kentucky, Delaware, and Maryland.

Another point of contention among the states revolved around the nature of the contract that bound them since 1787. The Northern states favored a federation, while the Southern states preferred a confederation.

However, merely listing the causes is insufficient to truly understand the origins of the conflict. Why were the North abolitionist and the South pro-slavery? Why did the South prefer a confederation over a federation?

To understand why the North and South were so divided, one must delve into the economic and commercial structure of these two Americas. Benefiting from a favorable climate, the South then thrived on vast fertile plains, naturally leading to its economy being dominated by the agricultural sector. However, as agriculture was unproductive and required abundant labor, the Southerners turned to slavery to enrich themselves. To sell their cotton and textile productions, the South heavily depended on European markets, naturally favoring free trade. This rural America was conservative and wary of the urban elites in the North, hence the reluctance towards a strong central government, fearing it would favor the interests of the "Yankees."

In contrast, due to a less favorable climate for agriculture, industrial activity flourished in the North. More modern, urban, and witnessing the emergence of a proletariat, a radically different society formed in the North. To develop these industrial capabilities, Northern politicians advocated for a strong central government and economic protectionism.

These vastly different economic specializations diverged the economic and political interests of the North and the South. As early as 1832, South Carolina threatened secession, bringing the country to the brink of civil war. Why? Because Congress, dominated by the North, imposed a tariff on manufactured goods from the Old World to protect the American industry. These tariffs indeed increased the price of consumer goods and raised the risk of European retaliation, to the detriment of Southern exports. The Congress's backpedaling ultimately saved the Union, albeit temporarily.

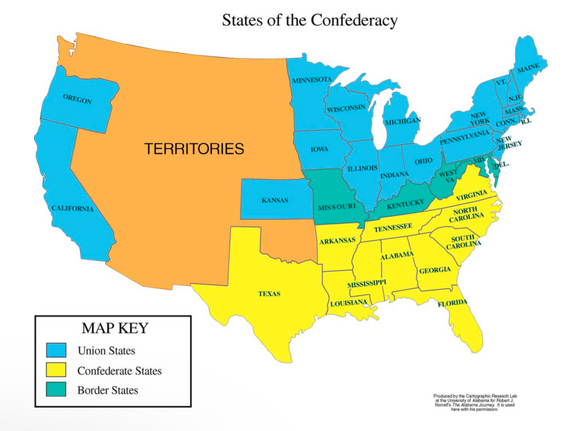

Ultimately, the Yankees' victory in 1865 and the abolition of slavery hastened the fall of the agrarian slave-based model in the South. Gradually, the South also industrialized. Among other things, the establishment of aerospace and defense industries gave rise, a century later, to the Sun Belt. While the scars of the Civil War have not disappeared, the North-South economic divide has considerably diminished.

So, what lessons can we draw from this historical example? First and foremost, the significance of the economic fracture between the North and South in the onset of the Civil War cannot be overlooked. Maintaining economic coherence and strong commercial ties within a country seems indispensable to ensure peace. The dreadful example of the Sudanese Civil War (1983-2005) reminds us of the dangers of excessive economic polarization within a country. While ethnic origin is often cited as the cause, it cannot overshadow the deep economic rift between a Southern region responsible for 85% of the country's oil production and a Northern region, where the only refineries (Port Sudan) and the sole export port concentrated, thereby monopolizing the created wealth. Such economic imbalances are sadly common, with examples like Cabinda in Angola or the Niger Delta in Nigeria, concentrating the bulk of their respective countries' oil wealth and still crystallizing tensions.

An overview over Haiti's current crises

On Friday the 04th of November, Haitian police finally liberated the country’s largest oil terminal from the control of gangs. This came at an essential time to revive the distribution of medicine and water in an effort to fight off the raging cholera epidemic, in a country that has been torn between political, humanitarian, and social crises, for the best part of the last decade.

Let’s take a step back. Haiti is densely populated with about 11 million inhabitants, most of whom are city dwellers. However, it is dealing with crippling inequality and poverty, with 70% of the population below the poverty line and 24% living in extreme poverty, while the rich own 63% of the country’s wealth despite making up only 20% of the population. The IMF ranks Haiti 163 out of 192 in terms of income per capita at purchasing power parity, lower than Irak, Tuvalu, or Micronesia. The same metric has been receding for now 4 years, and is now at its lowest point since 1994, erasing all the gains made in the aftermath of the recovery from the 2010 earthquake that killed north of 300 000.

This translates into several dramatic human challenges. Up to a quarter of the population suffers from hunger, and gangs have gradually grabbed more power and influence from the government to the point of becoming ubiquitous in people’s everyday lives. Following the 200% surge of killing, looting, and kidnaping under late President Moïse, Port-aux-Princes ended up looking like a warzone. Gangs’ exactions often go unpunished, and the still unsolved murder of Jovenel Moïse in July 2021 was followed by the birth of dozens of new ones throughout the country.

Consequently, citizens have had to learn how to live every day in fear of it being their last, and in constant shortage of basic services. They routinely have to evacuate their homes when gangs come to town and try to seek refuge at whoever wants to let them in, where they often have to sleep on the floor without knowing when they’ll be able to return home, if ever.

When Haitians get injured, they can only rely on few hospital beds. The country only counts one hospital bed for 1,502 inhabitants, one doctor for 3,353, and 124 reanimation bed in total. On top of that, health institutions, mainly private, lack life-saving equipment, medicine, water, and power access…Around three quarters of major hospitals are without power and unable to function.

How have we come to this? An important part of the answer to this question stems from Haiti's colonial past. From being where Columbus first landed in his 1492 inaugural Transatlantic voyage, it passed from Spanish to French rule in 1625, until becoming history’s only case of successful slave revolt and declaring independence in 1804. In 1825, Haitians agreed under threat to pay France hefty reparations for ending slavery back during the initial revolution. From 1915 to 1934 it was under US military occupation, and then under a dictatorship until 1986. Until now, the country has formally been a democracy. Yet, it has been led by corrupt governments, or disturbed by overturns and public outrages. Haiti accordingly ranks second on the scale of the most corrupt states in America.

This last fact only worsens Haiti’s economy by appearing as risky for potential investors: the structural instability scares them away and prevents the state’s economy from prospering. The inflation rate is dramatically high, and international help as well as money transfers from the diaspora are the main sources of income. Moreover, bordering countries try to protect themselves from immigration by erecting walls, as exemplified by the Dominican Republic.

With the government struggling to raise money, spending on education has been reduced to an unsustainable low. Only 62% of the population can read. Not only is the sector underfunded, but this year the start of classes has been delayed twice already, because of the oil shortage and the inability to ensure transportation.

Not providing the population with a proper education is not inconsequential. It contributes to the creation of improvised oil plants by citizens trying to earn their living. Nevertheless, it is frequent that these plants blow up, leaving many people severely burned.

Several organizations fight to regularize the situation in the archipelago, from attempts to forgive the national debt, to NGOs like MSF helping to save lives. But organizing this help turns out to be very tricky: MSF doctors are putting their life on the line, and gangs do not help them build safe zones for ambulances to cross through.

At the end of the day, all attempts to make things better in Haiti hinge upon the issue of gangs. With a weak government and the difficulty to funnel international aid, Haiti’s prospects look grim.